Louise X On View Gallery

Insomnia is a cruel possessor. You’re never really awake and you’re never really sleeping. Your current mood is surreal, dreamlike, and feels out-of-focus as everything mellows out somewhere around the middle.

It goes a little something like this, you lay down at a reasonable time-lights out, and wait...blink. Your mind snaps and sizzles and you wait for it to calm. But it doesn’t, in fact thoughts get increasingly louder. You think of everything, past and present and any possibility in the foreseeable future. After a while you get upset, which is understandable, because it goes on this way every night. Nothing’s relaxing, nothings calming, so you reach for your phone. Just a quick check, perhaps a little text to another insomniac friend. A Facebook update, Instagram login, Snapchat search...okay, just one quick game, maybe Solitaire or rather, Candy Crush. Or on second hand, let’s be productive. Let’s jump on the computer, do something like build a website from scratch, until the sun rises, your lovers’ alarm goes off, the dogs start to stretch. Now repeat that cycle every day for years on end. When do you think you would tire of it?

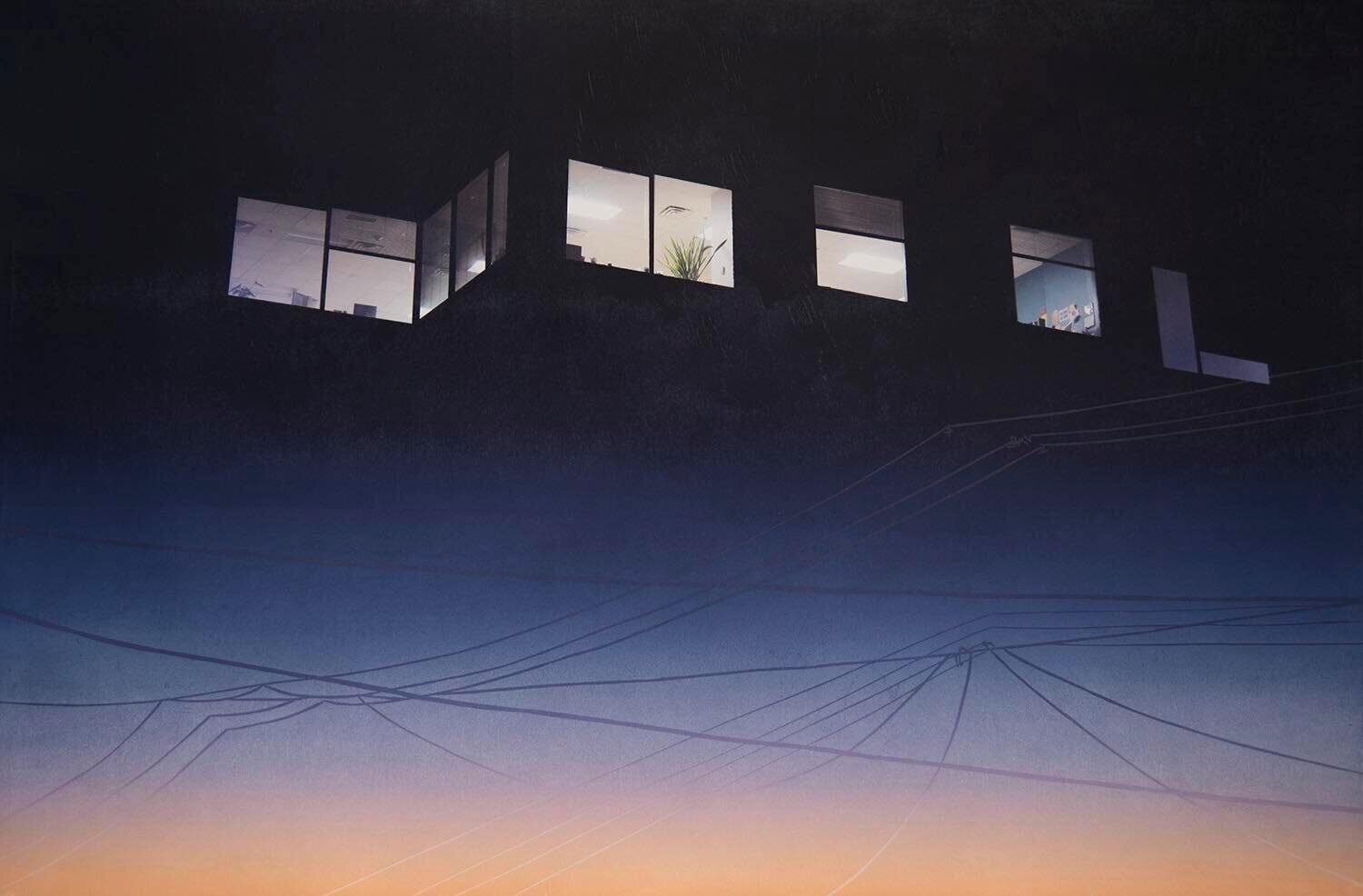

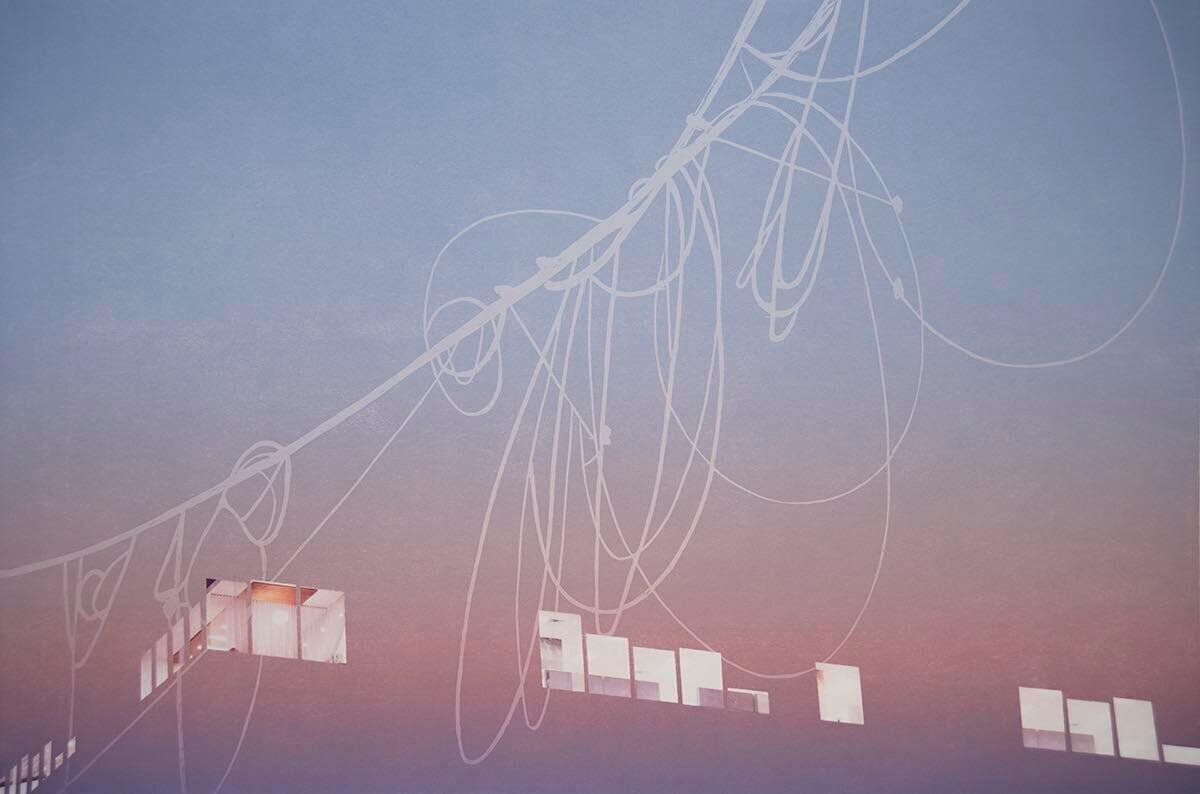

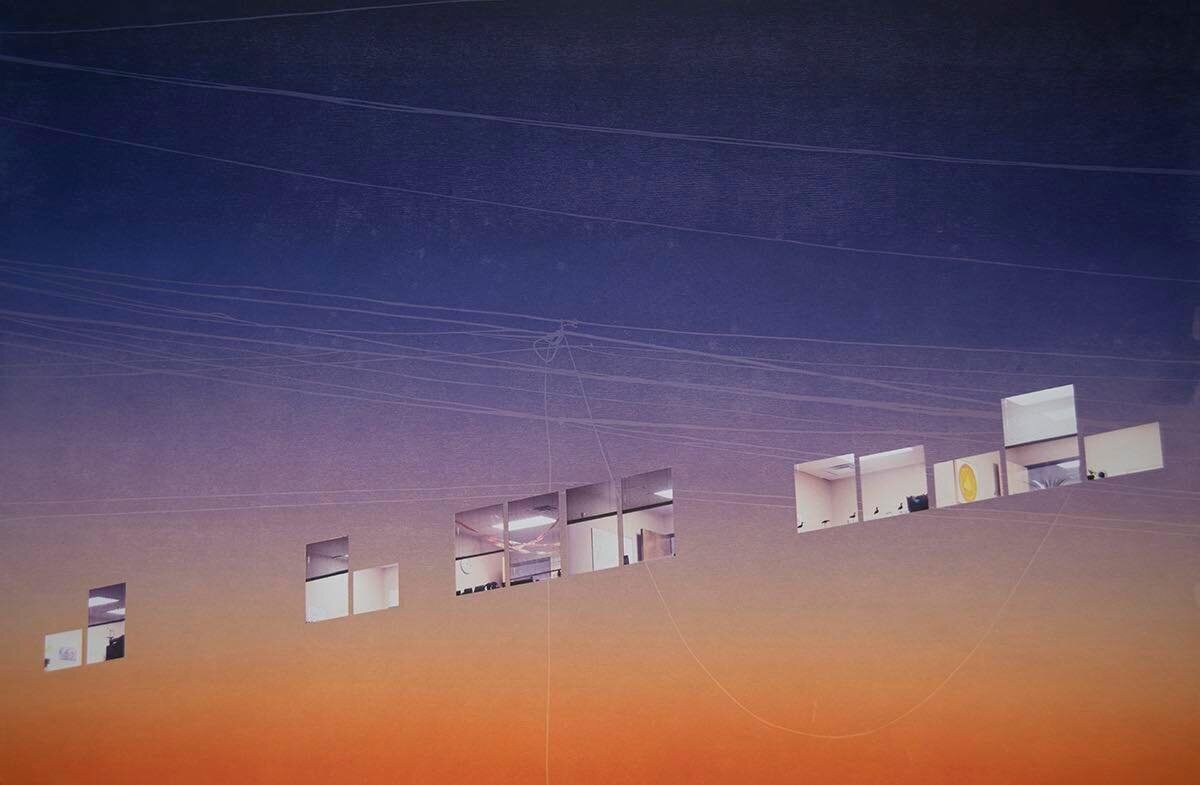

Louise Fisher is passionate about how artificial light affects our wellbeing and further implications of a tech-drenched society. Throughout her artwork she explores themes of connection/disconnection to nature, contrasts of natural light/artificial light and the juxtaposition of the natural world/man-made structures.

She was kind enough to answer some questions (not in her studio, social-distancing protocols were in place) about her teaching life, personal background and current exhibition.

***

Q.) What is your greatest lesson you’ve learned from teaching so far?

A.) My greatest lesson and challenge as a teacher is how to balance encouragement with high expectations. I see potential in every student and truly believe in their abilities, so my lesson plans are ambitious. My priority is giving them the confidence they need to be independent learners, and students gain confidence when they feel equally challenged and supported. My strategies include giving students choices, skill-building through exercises, emphasizing process, self-reflection, and practicing patience. Praising students on their work when they feel insecure can also go a long way.

Q.) If you had one piece of advice for any student of art, what would it be?

A.) The most important skill you can build as an art student is community-building. Sadly, most art students abandon their practice after graduation. There are several factors, but I contribute this to a lack of artist-to-artist relationships and access to resources (financial and spacial). Particularly as a printmaker who relies on a communal studio to accomplish her work, it’s hard to commit to your art when there’s no press. My artist friends keep me inspired and hold me accountable through conversation and critiques. Once you’re out of school, the soft skills of cooperation and friendship are useful because it’s easy to prioritize money over your studio practice. Also, American culture over-values individualism and competition, so I think whatever we can do to support one another as artists and maintain our relationships is healing and transformative. Artists are truly like family--our bond can transcend so many barriers!

Q.) Your pieces seem to be very thoughtful and intentional. How does your process help manifest that within your body of work?

A.) In my work everything is meaningful, and there is a marriage between process and concept. For years, I’ve been interested in the idea of time--this is why printmaking and photography are such important mediums for me. Printmaking allows me to make an impression endlessly and layer imagery, like the recalling of a memory. And there is a certain mindfulness in the process of printmaking, because it is an indirect, laborious and time-consuming process. This slowing down really allows me to be intentional. I consider woodcut my highest form of meditation. In the 24-7 Interior series, the power lines took an extreme amount of control and precision with my carving tool. I had to calm myself beforehand or else I got off track! There would be no fixing a miscut. Photography is a medium that exists solely because of light and time, which is directly related to my interest in biological rhythms. I have a bias toward analogue photography and shooting film. When shooting film, you have to understand how light (aperture) and time (shutter speed) work together to create an image since you can only use manual settings. Analogue photography also has the potential for experimentation, particularly in the darkroom--which I can’t get enough of. Even in digital photography, taking images becomes a heightened form of awareness. I often walk around the world with a photographer’s eye, seeing photographs as I notice my surroundings. I truly believe these technically-oriented processes give me such opportunity for playfulness and surprise even when I try to exert control. My scientific brain loves that.

Q.) In your work, there is a contrast of nature’s expression of light and of human expression of artificial light. It is done in an almost surreal yet familiar way, how did you discover you wanted to layer outside sunsets/sunrises and interior lighting?

A.) Reality lives somewhere between familiarity and illusion. I want viewers to think more critically about the urban spaces they’re in, so I do this by stipping away an element of the commonplace. Our cities would look like my artwork if the walls of buildings were transparent!

The idea of collaging skies with artificially lit windows came to me quite suddenly, but had been circulating in my subconscious for a while. In 2018, I was an artist in residence at the Picker’s Hut in Tasmania. The Picker’s Hut was very rural, and I lived in a one room cabin with no light pollution. Going from Phoenix to Tasmania and then back to Phoenix was really disorienting, but helped me put ideas into perspective. During my time at the Picker’s Hut, I became very interested in windows. The studio building had an entire wall of South-facing windows. I went there during the late fall, when the days were very short and I had to prioritize my schedule around sunlight. I often watched the curvature of the sun, rising in the East and setting in the West. Through that, I became highly aware of those transitional moments between day and night and the natural cycles of time. At night, when I would work in the studio with the lights on, I often spooked myself from my own reflection. For me, combining this juxtaposition of windows and sky represent a human defiance of the natural world, akin to a mental prison. I realized that windows have the ability to let light in during the day, but become light traps at night--you aren’t able to see the outdoors when artificial light reflects off the glass.

Q.) Do you feel growing up on a farm in Iowa impacted your relationship with nature and led to this knowingness of life without light pollution? And ultimately, do you have desire for humanity to reconnect with the rhythms of nature?

A.) I couldn’t possibly feel more passionate about any other question! My experience growing up in rural Iowa has informed everything I do. Immediate surroundings influence my artwork greatly, but being a child with full access to nature informs how I interpret those surroundings. As a rural person, I greatly value space, clean air, insects, plants, trees, stars, animals and spending quality time with family and neighbors. But I am also an artist, which causes me to feel and think deeply. My parents don’t really relate to my passion for dark sky preservation, but they are equally uncomfortable in urban environments. Intangible forms of pollution (such as air, light and noise) contribute to chronic disease, life expectancy and mental health disorders. I’m very interested in the research being done on how our artificial environments affect our well-being. Making others aware of these undercurrents could greatly help us lead healthy lives and coexist with other species.

When I lived on the farm, my summertime lullaby was the chorus of frogs and katydids outside my bedroom window. I often fell asleep on a trampoline underneath the stars with a perfect view of the Milky Way. Over the last ten years, there’s been a huge increase in urban populations and light pollution. Some children have never seen more than a handful of stars, and I am completely devastated by this. There are less and less places in the world where astronomers can study the night sky, where all of us can commune with the mystery of the cosmos. What can possibly be more humbling and comforting than a view of the stars? I see countless galaxies and know I’m not alone. And our disconnection from the natural world, from the stars or from wildlife, is greatly contributing to species loneliness. So yes, I want to dedicate my life to reconnecting people to the rhythms of nature so we can remember what it means to be human, to be whole. If we want to prevent ourselves from despair, it is going to be a critical component of the environmental movement for the next 5 years and art has a big role to play.